India’s Nuclear Budget 2026–27: What the Numbers Reveal

The global energy transition of the mid-2020s has produced many contradictions, but none are as stark or as lucrative as the "India Nuclear Paradox." Over the past five years, India has recorded the third-largest increase in power generation capacity globally, behind only China and the United States. In 2024 alone, 83% of power-sector investment flowed into clean energy, and India emerged as the world’s largest recipient of development finance, attracting approximately USD 2.4 billion in project-based clean-energy funding.

Yet despite this rapid scaling across nearly every segment of the energy system, nuclear power remains marginal—accounting for around 3% of India’s total electricity generation. For much of the international nuclear industry, this disparity reinforced the perception of India as a closed market: dominated by state monopolies and constrained by rigid, investor-unfriendly liability regimes.

For the international nuclear industry, this marginality has long been viewed as a sign of a closed market—a fortress of state-run monopolies and impenetrable liability laws. However, the events of 2025 have fundamentally re-engineered this narrative. With the passage of the landmark Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act in December 2025, India has effectively unlocked what is now the world’s largest untapped nuclear market, seeking over $214 billion in investment to reach a massive 100 GW target by 2047.

The Scale of the Prize

The fundamental driver of this opportunity is not just climate policy, but economic necessity. Government data show that electricity generation rose from 1,168 billion units (BU) in 2015–16 to an estimated 1,824 BU in 2024–25, yet grid stability has become increasingly strained. Although India has added more than 200 GW of renewable capacity, the inherent intermittency of solar and wind is now placing growing pressure on the country’s industrial base.

Heavy industries—aluminum smelting, steel production, and data centers—require firm, 24/7 power that weather-dependent sources cannot provide without massive, expensive battery storage. An aluminum smelter, for instance, requires 14–15 MWh per tonne of output throughout the day; there is no margin for the sun to set. This firm power gap is where nuclear’s value proposition has shifted from a strategic luxury to a commercial imperative. The Indian government now views nuclear energy not merely as a decarbonization tool, but as the only scalable, stable, and strategic solution for the next phase of its $30 trillion economic vision.

Why Nuclear Remained Small: The 60-Year Lock

To understand why this opportunity is only opening now, one must look at the structural cages that previously held the sector back. For sixty years, India’s nuclear story was defined by a state monopoly mandated by the Atomic Energy Act of 1962, which restricted all core activity to the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) and its commercial arm, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India Limited (NPCIL).

This "Sovereign Monopoly" model was limited by the state’s own balance sheet. Nuclear is the most capital-intensive form of power, with projects often costing between ₹16 crore and ₹20 crore ($1.8M to $2.2M) per megawatt. NPCIL simply could not move fast enough or mobilize enough capital to match India’s demand growth. Furthermore, the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage (CLND) Act of 2010 emerged as a structural barrier to international nuclear cooperation, as its supplier-liability provisions exposed foreign vendors, including Westinghouse and EDF, to open-ended financial risk beyond the scope of commercial insurance.

This created a paradox: a country with an insatiable hunger for power and a proven indigenous reactor technology (the 700 MWe PHWR) that was trapped in a legislative and financial dead end.

Union Budget headlines rarely move nuclear markets. Big numbers do, splashy missions do, and new reactor announcements do. Yet buried in the fine print of India’s Union Budget 2026–27 is a decision that may ultimately shape the commercial future of nuclear power in the country far more decisively than last year’s $2.21 billion Nuclear Energy Mission.

The government has quietly removed customs duties on critical imports for nuclear power projects until 2035—without restricting the benefit to any particular reactor size or technology. On its own, this looks like a routine fiscal tweak. In reality, it is a signal of something deeper: a deliberate attempt by New Delhi to re-engineer the cost, risk and market structure of nuclear power so that it becomes investable, bankable and scalable beyond state-led deployment.

Read alongside the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025 —which fundamentally rewrote India’s nuclear liability regime—and against the backdrop of surging industrial demand from data centres and energy-intensive industries, the customs duty exemption reveals a clear strategic pivot. India is no longer trying to “push” nuclear capacity through public sector balance sheets alone. It is trying to build a nuclear market—one that can attract private capital, global technology suppliers and long-term industrial offtakers.

Resetting the Cost Structure of Nuclear Projects

The budget reduces customs duty from 7.5 per cent to zero on goods imported for nuclear power generation falling under Harmonised System codes 8401 30 00 and 8401 40 00. The former covers non-irradiated fuel elements—metal cartridges containing fissile material—while the latter includes critical reactor components such as control and protection absorber rods and burnable absorber rods.

These are not peripheral inputs. They sit at the heart of reactor construction, commissioning and early operations. In large nuclear projects, imported fuel assemblies and reactor internals account for a substantial portion of capital expenditure. Even modest reductions in duties therefore translate into meaningful improvements in project economics, reducing upfront costs, tightening EPC bids and improving bankability for long-tenor financing.

Equally important is the breadth of the exemption. Unlike the Nuclear Energy Mission, which focused explicitly on small modular reactors, the customs relief applies to all nuclear power projects regardless of size. This signals a clear policy preference for a mixed deployment strategy—large reactors for grid-scale baseload generation and smaller reactors for captive, industrial and off-grid applications—as India works towards its stated target of 100 GW of nuclear capacity by 2047.

What the Nuclear Budget Actually Funds—and What It Doesn’t

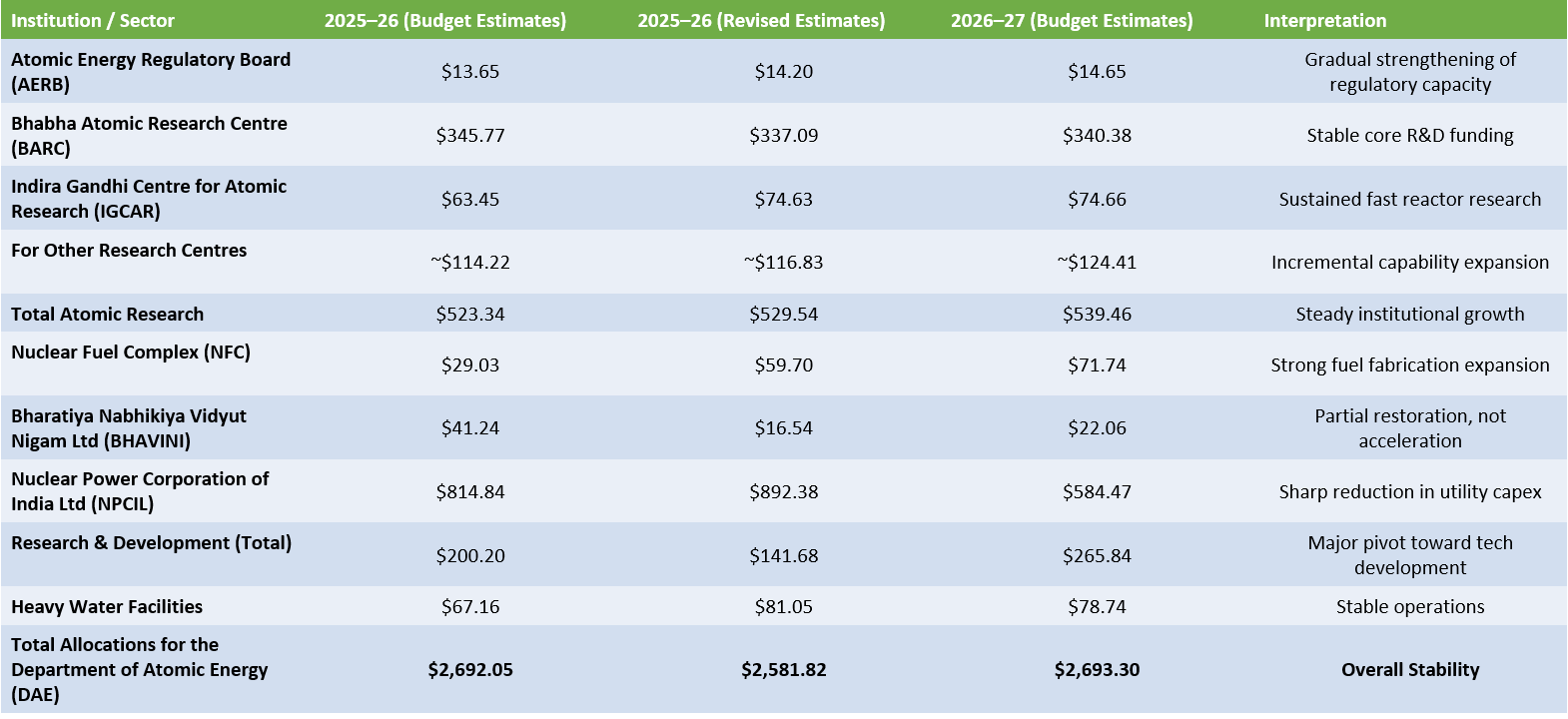

A close reading of Department of Atomic Energy allocations shows a clear pattern: institutional capability is being funded steadily, fuel cycle capacity is being strengthened, but utility-led reactor construction is being deliberately de-emphasised.

Comparative Allocations (USD Millions, net of recoveries/receipts)

The Most Important Number Is NPCIL’s Cut

The single most revealing line item in the 2026–27 nuclear budget is NPCIL’s allocation.

From $892.38 million in 2025–26 (Revised Estimates), NPCIL’s budget falls sharply to $584.47 million in 2026–27. This is not fiscal neglect. It is strategic intent. If New Delhi were planning to meet its long-term nuclear targets primarily through state-led construction, NPCIL’s capital allocation would be rising, not contracting. Instead, the government is signalling that NPCIL will no longer be the sole engine of capacity addition.

This explains why customs duty relief becomes so important. By lowering import costs while reducing direct public capex, the government is shifting the burden of expansion away from the exchequer and toward project-level economics—precisely what private capital requires.

Regulation, R&D, and Fuel: Building the Market Infrastructure

While NPCIL’s allocation contracts, three other areas quietly strengthened.

1. AERB: AERB’s steady rise to $14.65 million may look modest, but it is significant. A credible, well-resourced regulator is a precondition for private participation, especially for the Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), captive reactors, and foreign-supplied technologies.

2. R&D: Total nuclear R&D jumps 88% year-on-year to $265.84 million. This is not curiosity-driven science. It aligns with advanced reactor designs, fuel cycle optimisation, safety systems and digital instrumentation. In other words, the technology stack needed for commercial diversification, not just legacy PHWR deployment.

3. Fuel Cycle and NFC: NFC’s allocation rises to $71.74 million, more than doubling from the 2025–26 BE. This is a critical signal. As reactor ownership diversifies, fuel assurance becomes a sovereign concern. Strengthening domestic fabrication capacity is essential if India wants foreign reactors without foreign fuel dependence.

A Budget Signal Reinforced by Legislative Reform

The customs duty decision gains significance when read alongside the SHANTI Act, 2025, which replaced the Atomic Energy Act of 1962 and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act of 2010. The new legislation fundamentally reshapes India’s nuclear liability framework by aligning it with the 1997 Convention on Supplementary Compensation for Nuclear Damage. Liability for nuclear accidents is now channelled exclusively to plant operators, removing the supplier liability provisions that had long deterred foreign vendors, insurers and financiers.

Taken together, the duty exemption and liability reform alter both sides of the nuclear investment equation. Costs are lowered at the front end, while legal and insurance risks are clarified at the back end. For the first time, nuclear power projects in India can be evaluated on commercial terms comparable to other large infrastructure assets.

This is particularly relevant for private Indian companies and foreign suppliers considering joint ventures or long-term participation. The combined reforms create space for reactor vendors, fuel suppliers, EPC contractors and service providers to engage with the Indian market without the structural uncertainties that previously constrained participation.

Technology Choices and Supply Chain Integration

The evolving policy framework also has important implications for reactor technologies. India’s nuclear programme has historically been anchored in pressurised heavy water reactors, where domestic capability is well established. However, PHWRs represent a small share of the global reactor market.

By reducing import barriers and clarifying liability, the government is creating conditions conducive to greater engagement with light water reactor technologies through imports, licensed manufacturing or joint ventures. LWRs dominate international deployment and global supply chains. Mastery of these technologies would not only diversify India’s domestic reactor portfolio but also allow Indian firms to integrate more deeply into global nuclear value chains, both as suppliers and service providers.

In this context, the customs duty exemption functions not merely as a fiscal concession but as an enabler of technology transfer and long-term industrial integration.

Data Centres, SMRs and a New Demand Curve

Another budget announcement with direct relevance for the nuclear sector is the extension of tax holidays until 2047 for foreign cloud service providers that use data centre services from India. According to the Economic Survey 2025–26, India’s installed data centre capacity of 1.2 GW is expected to more than triple to around 4 GW by 2030.

Data centres are energy-intensive, operate on a 24/7 basis, and increasingly seek low-carbon power sources to meet sustainability commitments. This demand profile aligns closely with the capabilities of nuclear power, particularly small modular reactors deployed near industrial clusters or as captive generation assets.

Customs duty relief reduces the cost of deploying such reactors, while the SHANTI Act clarifies ownership and liability structures. Together, they make nuclear power a more credible option for meeting the growing energy needs of India’s digital economy.

Reviving Global Nuclear Partnerships

The combined impact of budgetary and legislative changes is also likely to reshape India’s global nuclear partnerships. While cooperation with Russia and France has continued, engagement with the United States remained constrained for years due to liability concerns under the previous legal framework.

With the SHANTI Act now in force and customs barriers lowered, India–US nuclear cooperation is poised for revival. This assumes added significance as both countries move towards a broader trade agreement aimed at reducing tariffs and expanding bilateral commerce. Nuclear trade—high-value, technology-intensive and long-term by nature—stands to benefit disproportionately from such a reset.

For US suppliers of reactors, components and nuclear services, India once again emerges as a credible market. For Indian firms, renewed engagement offers access to advanced technologies, financing mechanisms and export opportunities.

A Business-First Nuclear Strategy Takes Shape

The customs duty exemptions announced in Budget 2026–27 should not be viewed in isolation. They are best understood as part of a policy sequence that began with the Nuclear Energy Mission in the 2025–26 budget and culminated in the passage of the SHANTI Act. Together, these measures signal a clear strategic shift: India is no longer seeking to expand nuclear power primarily through public spending or state-led construction, but through a market-oriented framework designed to attract private capital, absorb global technology, integrate into international supply chains, and respond to emerging industrial demand.

In this context, the 7th edition of the India Nuclear Business Platform (INBP), scheduled for 16–17 June 2026 in Mumbai, assumes particular strategic significance. As the first major global convening following these landmark reforms, INBP 2026—under the theme “India’s Nuclear 100: Delivering the $200 Billion Opportunity”—marks a shift from policy discourse to commercial engagement, offering international vendors, investors, and EPC players direct access to India’s newly authorised private category of industrial groups empowered to finance, construct, own, and operate nuclear assets. For nuclear businesses, domestic and international alike, this is what makes Budget 2026–27 truly consequential: not the scale of public spending it announces, but the market architecture it quietly puts in place.